Introduction: The Enigma of Dalí

Salvador Dalí wasn’t just an artist—he was a phenomenon, a figure as surreal as his own art. There was something in him that defied categorization, that made him seem like both a genius and a madman, both grounded and entirely untethered from reality. He seemed to live by his own rules, bending reality around him like the melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory. And yet, he claimed to be anything but mad. “The difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad,” he once said, as if daring us to understand the boundary between himself and the chaos he embraced.

Dalí’s life was an extension of his art, or maybe it was the other way around. The line blurred so much that it’s hard to say where one began and the other ended. For him, art wasn’t confined to the canvas. It spilled over into his life, his personality, even his fashion choices. Whether he was designing surrealist jewelry, collaborating on dream sequences in Hitchcock’s Spellbound, or posing with an anteater on a leash, Dalí was creating art in everything he touched. He seemed determined to show the world that creativity had no boundaries, that it could be found in the strangest, most unexpected places.

But what really makes Dalí fascinating—beyond the eccentric persona, the theatrical mustache, and the wild public stunts—is the way he approached reality itself. At the core of his art was something he called the “paranoiac-critical method.” It was his way of diving into the subconscious, of finding hidden connections between things that seem totally unrelated. Dalí believed that if you could look at the world through a controlled state of paranoia, you’d see patterns and connections that others couldn’t. It’s almost like he thought the universe was speaking a language that most people weren’t attuned to, and he found a way to listen.

Dalí’s legacy goes beyond his famous paintings and extends into this strange, almost mystical perspective he brought to the world. As we explore his life and work, we’ll see how his art, his eccentricity, and his paranoiac-critical method weren’t just aspects of his creativity—they were his way of life. He lived as though reality was just a canvas, ready to be stretched, twisted, and reimagined.

In Dalí’s world, art wasn’t something confined to galleries or museums. It was everywhere, and he dared us to see it that way, too. Maybe that’s the true legacy he left behind: an invitation to embrace the strange, to find beauty in the unexpected, and to let our imagination run wild, just as he did.

Part One: Dalí Beyond the Canvas – Exploring His Versatility

For many people, Salvador Dalí is synonymous with surrealism. We think of his melting clocks, his barren landscapes, and his peculiar, almost haunting symbols. But Dalí’s vision went far beyond the confines of any one medium. He wasn’t content to let his ideas live only on canvas. Instead, he treated every creative field he touched as just another extension of his surrealist playground. And, in true Dalí fashion, he brought that same blend of beauty and strangeness to everything he created.

Take his work in jewelry design, for instance. Dalí’s pieces aren’t just jewelry—they’re miniature, wearable works of art, each infused with that surrealist touch. One of my favorites is The Eye of Time, a brooch shaped like an eye, with a clock in place of the iris. It’s both eerie and captivating, a reminder that even time itself isn’t as straightforward as it seems. In Dalí’s hands, an eye isn’t just an eye, and a clock isn’t just a clock. They’re symbols, woven together in a way that invites us to question how we perceive time, vision, and maybe even reality itself.

Then there’s The Royal Heart, another surrealist masterpiece in miniature. Made of gold and encrusted with rubies, it’s designed to look like a heart—and not just any heart, but a living one. The rubies shimmer like droplets of blood, adding a lifelike quality that’s both beautiful and unsettling. It’s surrealism in its purest form, taking something familiar and twisting it just enough to make you see it differently.

But Dalí’s reach didn’t stop with objects. He ventured into film, working with Alfred Hitchcock on the dream sequence in Spellbound. If you’ve seen the film, you know the scene—filled with eerie eyes, looming shadows, and surreal landscapes. That dreamlike quality, the sensation of being in a place both real and unreal, is pure Dalí. He used the paranoiac-critical method to bring those images to life, turning Hitchcock’s suspense into something that feels like a descent into the subconscious.

And then there’s his collaboration with the photographer Philippe Halsman. Together, they created iconic images that are as memorable as any of Dalí’s paintings. One of the most famous, Dalí Atomicus, captures Dalí in mid-air, paintbrush in hand, while furniture, cats, and water all seem to be suspended in a moment of chaotic weightlessness. It’s as if the laws of physics took a step back to make room for Dalí’s vision of pure, suspended surrealism.

What strikes me most about Dalí’s work across all these mediums is how he approached each one with the same fervor, the same desire to blur the lines between reality and imagination. He didn’t care if it was a painting, a piece of jewelry, a film, or a photograph—it was all just another layer of his surreal universe. He showed us that art doesn’t have to be confined to a single form, and that creativity can, and maybe should, spill over into every corner of life.

For Dalí, the world was a canvas, and he was always painting on it, reshaping it in his image. His work beyond the canvas isn’t just a collection of “side projects”; it’s a testament to his belief that reality itself is flexible, that everything—whether it’s a film sequence or a piece of jewelry—can be made surreal.

Part Two: The Madman Behind the Art – The Duality of Dalí

There’s no talking about Salvador Dalí without addressing the eccentric persona he created for himself. Dalí wasn’t just a surrealist artist—he was the surrealist artist, a living, breathing embodiment of his work. The way he dressed, the way he spoke, even the way he carried himself—it was all part of a larger-than-life character that blurred the line between who he was and who he wanted the world to see.

Dalí didn’t just create surreal art; he made his life surreal. He turned himself into a kind of art piece, one that was as puzzling and provocative as his paintings. He arrived at events in a diving suit, complete with a helmet, declaring that he wanted to “plunge deeply” into the human mind. He kept an anteater as a pet and would occasionally take it on leashed walks around Paris. He once famously said, “I am not strange. I am just not normal.” It’s almost as if he was challenging everyone around him to question what it meant to be “normal” in the first place.

And then there’s that quote—“The difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad.” It’s a line that captures the essence of Dalí’s public persona perfectly. Dalí wanted people to think he was mad, but only on his terms. He walked the line between genius and insanity, leaning just far enough into madness to keep people guessing. For him, madness wasn’t a flaw; it was a tool, a way to push his creativity to extremes. And he made sure to stay just on the right side of it, carefully controlling the image he projected to the world.

But here’s where it gets interesting: it wasn’t all an act. Yes, Dalí knew how to put on a show, but there was something genuine beneath all the eccentricity. He understood the power of perception, of creating a mystique around himself that blurred reality. He was a master of turning himself into a story, weaving myth into his own life. In a way, his personality became an extension of his artwork—a living surrealist piece that challenged the boundaries of what’s real and what’s staged.

Dalí didn’t hide his eccentricity; he flaunted it. He seemed to know that the world often associates genius with madness, and he used that association to his advantage. He gave people what they wanted, but he did it in his own way, on his own terms. He was in control, crafting a character who could step into the bizarre and still keep his footing. It was as if he was saying, “Yes, I’m strange, but there’s a method to my madness.”

So, was Dalí truly mad? Or was he just playing a part? Maybe it was both. Perhaps he saw himself as a kind of shapeshifter, someone who could slip between the roles of artist, genius, and madman at will. He understood that people are drawn to mystery, to things they can’t fully explain, and he gave them that. But he also held onto his own sense of identity, remaining anchored to something that let him keep pushing his art to new, surreal extremes.

The result? Dalí became a surrealist icon not just for his art, but for the way he lived his life. He turned himself into a character that people would never forget, a figure as enigmatic and layered as his paintings. And perhaps that was the point all along—to live in such a way that he became part of his own myth, part of the surreal world he wanted everyone to see.

Part Three: The Paranoiac-Critical Method – Dalí’s Surrealist Vision

For most artists, creativity is about connecting with inspiration, tapping into a personal wellspring of ideas and emotions. But Salvador Dalí had a different approach—one that was both methodical and strange, something he called the “paranoiac-critical method.” This was Dalí’s way of diving into the subconscious, a technique he developed to see the world from a perspective that was both unsettling and deeply surreal.

The paranoiac-critical method isn’t easy to define, and that’s part of its power. At its core, it’s about embracing a controlled state of paranoia, a way of looking at the world where connections appear that don’t exist in reality but feel profoundly real in the mind. Dalí described it as a way of finding hidden links between unrelated things, almost as if pulling at invisible threads that tie together the logical and the irrational, the conscious and the subconscious. For Dalí, this method wasn’t just a creative exercise; it was a philosophy, a new way of experiencing reality.

Imagine looking at a familiar object—say, a rock or a piece of driftwood. In a normal state of mind, it’s just that: a rock, a random shape formed by nature. But under Dalí’s paranoiac-critical lens, that rock might start to resemble something else entirely. Maybe it takes on the form of a face, or the silhouette of a creature, or some strange symbol that feels like it holds hidden meaning. Dalí trained himself to see these connections, to let his mind roam freely across the boundaries of reality, creating a world where the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and the real blends seamlessly with the surreal.

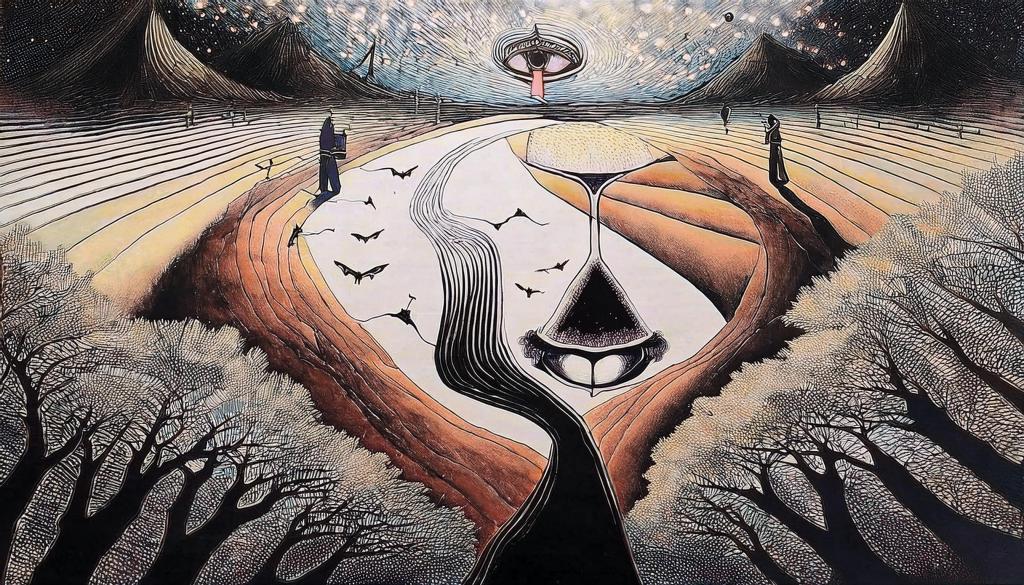

This method was more than a mental exercise—it was a gateway into Dalí’s art. Take The Persistence of Memory, for instance. Those melting clocks aren’t just clocks; they’re symbols of time’s fluidity, of how memory can distort reality. They might not make logical sense, but under Dalí’s paranoiac-critical method, they’re completely at home. In Dalí’s world, logic is just another canvas, stretched and shaped into something that defies explanation yet feels intuitively true.

The paranoiac-critical method was Dalí’s way of tapping into the subconscious, almost like lucid dreaming. It’s as if he was awake, but his mind was still wandering through a dreamscape, pulling bits and pieces of surreal imagery back into the waking world. This approach let him see the hidden relationships between things, finding meaning in randomness and chaos. In Dalí’s hands, the world became a puzzle with endless layers, each one stranger and more intriguing than the last.

What’s fascinating about Dalí’s method is that it wasn’t confined to his art. It was a mindset, a way of moving through life with eyes wide open to the strange and the unexpected. He believed that by adopting this state of controlled paranoia, anyone could begin to see the world in new, surreal ways. To Dalí, reality was just the surface layer of a much deeper, more interconnected web of meanings and symbols—a web that only the paranoiac-critical mind could begin to unravel.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Dalí’s Surrealism

Salvador Dalí left behind more than just a collection of surreal paintings; he left a vision, a way of seeing the world that invites us to question everything we think we know. Through his work across so many mediums, his eccentric personality, and his paranoiac-critical method, Dalí created not just art, but an entire philosophy. He showed us that reality is never as fixed or solid as it seems—that beneath the surface of the ordinary, there’s a world of endless possibility waiting to be uncovered.

Dalí’s legacy is a testament to the power of embracing the strange, the unconventional, and the irrational. He lived his life as if the entire world was a canvas, constantly blurring the lines between art and reality, madness and genius. His flamboyant persona, his meticulously crafted surrealist “character,” and his belief in controlled paranoia all encouraged us to look beyond the familiar and embrace the bizarre. For Dalí, the imagination wasn’t something to be confined to a studio or gallery; it was something to be lived, to be felt in every corner of existence.

In today’s world, where the boundaries between the real and the virtual continue to blur, Dalí’s vision feels more relevant than ever. He reminds us that creativity doesn’t just come from skill or technique; it comes from daring to see the world differently, from allowing ourselves to play with ideas that don’t seem to make sense on the surface. His work urges us to find beauty in the unexpected, to see connections where others see chaos, and to view reality not as a fixed structure but as a flexible canvas for our own ideas and dreams.

Dalí’s surrealism isn’t just an art movement—it’s an invitation. It’s a challenge to think, to dream, to live in ways that are bold and unexpected. As he showed us, the world is full of hidden patterns and strange connections waiting to be discovered. And maybe, just maybe, if we adopt a bit of that paranoiac-critical mindset, we can start to see those connections, too.

In the end, Dalí’s greatest masterpiece may have been himself: a living symbol of surrealism, a figure who turned his life into art and his art into life. He left us with a legacy that goes beyond paintings and sculptures. He left us with a vision of what it means to live creatively, to inhabit a world where reality is just the beginning, and imagination is limitless.

Leave a comment